Treasure Stories

by James M Deem

Lost Treasure of the Bighorn River

Missing Treasure of Clifford, Colorado

Back to Main Treasure Stories

Other Recommended Treasure Books

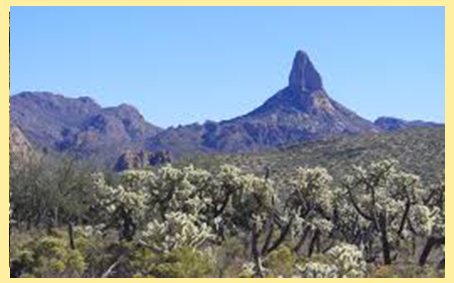

One legendary treasure that has led many astray and ruined lives is the Lost Dutchman Mine, supposedly located in the Superstition Mountains east of Phoenix, Arizona. As with most legends, there are many discrepancies among the various accounts. According to Helen Corbin, author of The Curse of the Dutchman's Gold, in 1846, a man named Jacob Waltz emigrated from Wurttemberg, Germany, to the United States. After he became a naturalized American citizen in July 1861, he traveled to Arizona and became a prospector. Sometime between 1872 and 1878, Waltz and his partner, Jacob Weisner, reportedly found gold in an eighteen-inch-wide vein of quartz. They mined some ore and placed it in a cache near the mine. One day, while working on the mine, Weisner was killed by the Apaches.  Upset by Weisner's death, Waltz never filed a claim for the mine. He concealed its entrance, took only the ore that he needed to live on, and moved to Phoenix, where he lived in an adobe house on a small farm near the Salt River.

Upset by Weisner's death, Waltz never filed a claim for the mine. He concealed its entrance, took only the ore that he needed to live on, and moved to Phoenix, where he lived in an adobe house on a small farm near the Salt River.

There, he earned his living by delivering fresh eggs to a woman named Julia Thomas, who owned a local bakery and knew nothing of Waltz's mine. One day in 1891, Waltz discovered that Julia was in debt and in danger of losing her bakery, and he offered to help her repay her debts. Until the moment that he showed her gold ore worth about $1,500, Julia thought he was a poor farmer.

Waltz told her that he would ship the gold to a smelter in San Francisco. "I've shipped gold from Casa Grande in the past," he said. "I'm familiar with the procedure. When the money comes back, I'll lend most of it to you."

He continued:

There's a great deal more where that came from.... It's in a cache that we made, my partner and 1. The gold came out of a mine, of course. I have the right to work that mine, but I gave that up after my partner was killed. He was killed by the Apaches twenty years ago, and I never wanted to work in the mine again. Anyway, I'm getting too old for that kind of thing now.

He promised to share the wealth of the mine with Julia and her adopted son, Rhinehart Petrasch. They planned a trip into the Superstitions during the spring of 1892 to retrieve the rest of the gold in Waltz's cache. Unfortunately, Waltz's house was swamped that summer when the normally dry Salt River was flooded with runoff from torrential rains. Waltz caught pneumonia from his drenching and died on October 25, 1891, months before he could take Julia and Rhinehart into the Superstitions. Shortly before his death, he reportedly told them that a small amount of gold ore was hidden beneath his fireplace and he sketched a map giving the location of the mine. Not only did they not find the mine, they were even robbed of the gold ore that Waltz had left them.

The bare-bones account of this story has been enough to send thousands of treasure hunters into the Superstitions, where some have died, sometimes under mysterious and rather gruesome circumstances. For most searchers, greed replaced common sense--except in a few treasure trackers.

One searcher who took a different approach is Bob Corbin, who has hunted for the legendary mine since 1957. As a child in rural Indiana, Corbin wasn't particularly interested in finding treasure, but while serving in the Navy around 1948, he read a magazine article about the fabled mine. The article interested Corbin enough to change the course of his life: he decided to move to Arizona and tackle the Lost Dutchman.

A greedy treasure hunter would have made plans to head for Arizona immediately, but not Corbin. He had obviously learned something from the mistakes of many others. Searching for the Lost Dutchman Mine was to become his hobby, not his primary occupation. First, after leaving the Navy, he went home and earned a college degree at Indiana University. After that, he completed a law degree.

Only then, in June 1957, nine years after he had decided to look for the Lost Dutchman Mine, did Corbin move to Arizona, ready to practice law and start his treasure-hunting hobby. On his first weekend there, he went into the Superstition Mountains. As an inexperienced desert dweller, he hadn't thought much about Arizona summers. He quickly learned that the best time to prospect was winter, when temperatures were lower and ground water was plentiful. He also learned that further research was in order.

But he had work to do. Besides occasional trips into the Superstitions, Corbin was a county attorney and eventually served as the Arizona attorney general from 1979 to 1991. Even with such demanding jobs, Corbin found time to pursue his hobby.

He and his partner, Tom Kollenborn, have spent more than thirty years poring over documents and old newspapers, trying to prove the basic outline of Jacob Waltz's story. During this time, Corbin went through different phases. Sometimes he believed the mine was real, sometimes not. Once, when he doubted its existence, he did not set foot in the Superstitions for seven years. Now, however, the two partners' research has convinced him that there is a mine, although it has been filled in or otherwise obscured.

Many treasure trackers would be disappointed at not finding a gold mine after thirty years' work, but not Corbin. What he enjoys is the search. It gives him the opportunity to get outdoors, away from the pressures of work, and the chance to sit by a campfire, cooking his dinner and gazing at a wide sky. After all, Corbin explained, "you can see so many more stars in the mountains."

What's more, he has developed a hobby that builds on his skills as a lawyer. In both instances, he sifts through evidence, looking for facts, checking for discrepancies. He follows up on hunches and asks tough questions. In his vocation and his avocation, he relies on his inquisitive mind, as all successful treasure trackers should.

Copyright © James M. Deem. Taken from How to Hunt Buried Treasure (Houghton Mifflin, 1994). All rights reserved.