Treasure Stories

by James M Deem

Lost Treasure of the Bighorn River

Missing Treasure of Clifford, Colorado

Back to Main Treasure Stories

Other Recommended Treasure Books

Although treasure stories may lead to the same conclusion--that gold or silver is buried somewhere--they may have different versions, and a treasure seeker can become quite perplexed. Such is the case with a treasure associated with the death of General George Armstrong Custer.

For many Americans living in 1876, the western part of the United States held the promise of great riches. Gold had been discovered in California, and in the early 1870s many were certain that huge amounts of the ore would be found in Montana and the Black Hills of South Dakota. Some small gold claims had already been filed there, but few struck it rich.

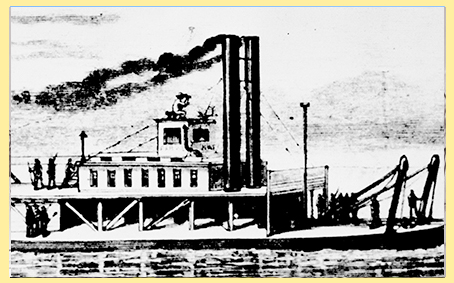

What the miners didn't know is that a lost shipment of gold was - and may still be - buried near the Little Bighorn battle site. When Custer and his men died on June 25, 1876, a steamboat named the Far West was making its way up the Bighorn River. Under the command of Captain Grant Marsh, the Far West had orders to follow the Bighorn River to the mouth of the Little Bighorn. Captain Marsh was then to guide the boat fifteen to twenty miles upstream and rendezvous with General Alfred H. Terry and resupply his troops. As the boat sailed to its destination, word reached Captain Marsh that Custer and his men had been massacred and that wounded soldiers would be brought to the Far West and taken to Fort Lincoln, near Bismarck, North Dakota.

What the miners didn't know is that a lost shipment of gold was - and may still be - buried near the Little Bighorn battle site. When Custer and his men died on June 25, 1876, a steamboat named the Far West was making its way up the Bighorn River. Under the command of Captain Grant Marsh, the Far West had orders to follow the Bighorn River to the mouth of the Little Bighorn. Captain Marsh was then to guide the boat fifteen to twenty miles upstream and rendezvous with General Alfred H. Terry and resupply his troops. As the boat sailed to its destination, word reached Captain Marsh that Custer and his men had been massacred and that wounded soldiers would be brought to the Far West and taken to Fort Lincoln, near Bismarck, North Dakota.

The story of the Far West becomes confusing at this point. Some researchers agree that gold was on board the supply boat, but they disagree on how it got there. What's more, they agree that the gold was buried onshore, but they disagree on its precise location. In fact, two stories have been told to account for the appearance - and disappearance - of the Far West gold.

Treasure Tale 1: Gold bars from Williston

According to an account by writer Emile Schurmacher in his book Lost Treasures and How to Find Them,  Captain Marsh had taken the boat to Williston, North Dakota, where it had collected a shipment of gold bars worth $375,000 and then left for its rendezvous with General Terry. The gold was to be delivered to Bismarck on the return trip.

Captain Marsh had taken the boat to Williston, North Dakota, where it had collected a shipment of gold bars worth $375,000 and then left for its rendezvous with General Terry. The gold was to be delivered to Bismarck on the return trip.

After fifty-two wounded men were brought on board to make the 740-mile trip to Bismarck, Marsh realized that he would need all the room he had on board for firewood to fuel the steamer's engine. The gold would have to be buried ashore temporarily; he could return later to collect it.

Schurmacher says that Marsh twice attempted to retrieve the gold. Once, two months after it was hidden, he docked the boat in the same location. He could identify the site because tree stumps indicated where the crew had cut firewood to make the return journey to Bismarck. Unfortunately, heavy rains had caused a mud slide to wash over the burial site. Despite considerable digging, he and his men were unable to find even one bar of gold.

Treasure Tale 2: Gold nuggets from Bozeman

The other account, by writer Roy Norvill in his book The Treasure Seeker's Treasury, is more dramatic.  In it, Captain Marsh encountered three men on the evening of June 26, the day after Custer's death. Marsh had not yet learned of the massacre, but he knew that many Sioux were in the area. The men shouted to Marsh from the riverbank. They were Gil Longworth, a wagon driver, and Tom Dickson and Mark Jergens, his guards. They were carrying a shipment of gold nuggets from Bozeman, Montana, to Bismarck. Longworth was worried that he would be attacked by the Sioux and would never deliver the gold shipment, so he begged Marsh to take it on board the Far West.

In it, Captain Marsh encountered three men on the evening of June 26, the day after Custer's death. Marsh had not yet learned of the massacre, but he knew that many Sioux were in the area. The men shouted to Marsh from the riverbank. They were Gil Longworth, a wagon driver, and Tom Dickson and Mark Jergens, his guards. They were carrying a shipment of gold nuggets from Bozeman, Montana, to Bismarck. Longworth was worried that he would be attacked by the Sioux and would never deliver the gold shipment, so he begged Marsh to take it on board the Far West.

After it was transferred to the ship, Longworth, Dickson, and Jergens headed back to Bozeman on land, a route they considered safer. But Captain Marsh had second thoughts about keeping the gold on board. As he watched the smoke from many Sioux campsites that night, he concluded that it would be safer to hide the gold ashore and return for it later. This was accomplished the same night.

In the next few days, the wounded soldiers were brought to the steamer and Marsh learned the fate of the three men from Bozeman: All three were killed by the Sioux. Dickson and Jergens died at Pryor's Creek; Longworth's body was found a few days later at a spot known as Clark's Fork. Apparently, he had escaped the Sioux but had been mortally wounded in the process.

Norvill writes that, although Marsh never forgot about the gold, he made no attempt to recover it. He was afraid that a return trip would be too risky. In 1879, however, he visited Bozeman to find the freight company that had hired Longworth. Unfortunately, the company had long since closed.

Two stories - and two versions of how the gold came to be on board the Far West and where it was buried.

Is either story true? Did Marsh load a shipment of gold bars in Williston, or did he accept a frightened driver's load of gold nuggets from Bozeman? Did he bury it on the Bighorn River, as Schurmacher claims, one-half mile from the Yellowstone River? Or did he bury it,as Norvill says, fifteen to twenty miles up the Bighorn River from the mouth of the Little Bighorn? Could there be two gold treasures? Or did one or both writers concoct intriguing stories?

Two things can be said for certain. First, Captain Grant Marsh and the Far West were real. Second, both helped in the evacuation of wounded soldiers and sailed the Bighorn and Little Bighorn rivers at the time of Custer's death.

Beyond that, however, nothing is clear. Although many people believe that a cache of gold is buried along the Bighorn River, a treasure tracker interested in this case should do a lot of library research before making a trip to the Bighorn River.

Copyright © James M. Deem. Taken from How to Hunt Buried Treasure (Houghton Mifflin, 1994). All rights reserved.