On a hot and somewhat overcast August 10, 1901, two English schoolteachers named Anne Moberly and Eleanor Jourdain visited the Palace of Versailles on their vacation to Paris. About four o'clock that afternoon, after touring the palace and taking some refreshment at the Salle des Glaces, they set off for a walk around its spacious grounds.  In particular, they wanted to visit another house on the property known as the Petit Trianon.

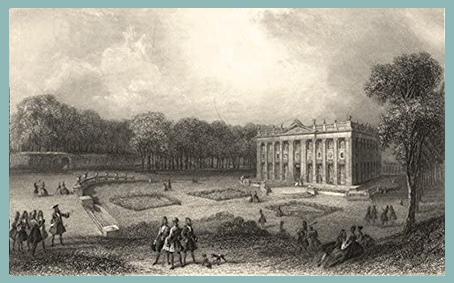

In particular, they wanted to visit another house on the property known as the Petit Trianon.

The day itself was not unusual, but their experiences, which they later described in their book An Adventure, were, though they didn't realize it immediately. Here are the facts of their adventure, which has become one of the most famous time travel stories ever:

The Petit Trianon is almost a mile from the palace, and the two women were unfamiliar with its location. Although they used a map, they "began talking about our mutual acquaintances in England and paid but little attention to our surroundings." In short order, they became lost and found themselves circling an unfamiliar complex of buildings.

There, they saw two men. Because one was holding a spade and a wheelbarrow was nearby, they appeared to be gardeners, except that, Miss Moberly recalled, they were dressed like "very dignified officials." Each was wearing a long grayish green coat and an old-fashioned tri-cornered hat. They stopped to ask the men for directions and were instructed to walk "straight on."

As they continued down the path, Miss Moberly was aware of an "extraordinary depression" coming over her. There was no reason for her change in mood, she believed. The walk was enjoyable even if they had become lost. The sun was shaded with clouds and a breeze was blowing. But something wasn't right. What's more, her companion, Miss Jourdain, also sensed "a depression and a loneliness" about her surroundings.

Shortly, after making another wrong turn, they came upon a gazebo-like structure. A man with a rough dark complexion and a "repulsive face" was seated on the railing. Upon seeing him, Miss Jourdain's depression changed to fear. She was certain that the man was "very evil," so she ignored him, as did Miss Moberly, and they continued on their way.

Suddenly a man ran up behind them, calling, "Mesdames, mesdames."

He was tall and handsome and wore a large sombrero and a heavy black cloak. He had been running so hard that his face had turned bright red--so red in fact that Miss Moberly thought, How sunburnt you are! even though she realized that his face was not really sunburned at all. Rather, it seemed to have that rosy-cheeked look a person gets outside on a cold day.

He spoke quickly in French and gestured to the women, but they had trouble understanding him. He seemed to indicate that they should head right and cross a bridge. Later, though, Miss Moberly recalled that he had said something about "looking for the house...."

They followed what they took to be his directions, and in moments they arrived at the back of the Petit Trianon. There, Miss Moberly saw a woman seated on a chair beneath the balustrade of the rear terrace. Miss Moberly wrote that the woman was either sketching or reading.

Here is how she described the woman later:

She had on a shady white hat, perched on a good deal of fair hair that fluffed around her forehead. Her light summer dress was arranged on her shoulders in handkerchief fashion, and there was a little line of either green or gold near the edge of the handkerchief... Her dress was long-waisted, with a good deal of fullness in the skirt .... I thought she was a tourist, but that her dress was old-fashioned and rather unusual.

Surprisingly, she later discovered that Miss Jourdain had not seen the woman.

As the two women walked toward the stairs that led to the rear terrace, the seated woman turned to look at Miss Moberly. Miss Moberly noticed that the woman was not young and that "there was something unattractive about her appearance."

They toured the house and afterward had tea at a local hotel before returning to Paris. But they never once discussed their experiences that afternoon at Versailles. In fact, for a week, neither Miss Moberly nor Miss Jourdain spoke to each other about their visit.

Finally, Miss Moberly asked her friend, "Do you think that the grounds of the Petit Trianon are haunted?"

"Yes, I do," replied Miss Jourdain.

That question prompted them to reconsider their walk, but in a leisurely fashion. Although the women talked about their visit that day, they did not discuss it again until three months later, when Miss Jourdain went to see Miss Moberly at her Oxford, England, home.

During this visit, Miss Moberly referred to the woman sitting at the back of the Petit Trianon. Miss Jourdain insisted that she had seen no such woman. They realized that each of them might have experienced something different, so they decided to write separate accounts of what had happened that day. They also decided to research the history of the Petit Trianon to see if it was haunted. Eventually, they would agree that they had traveled back in time 109 years.

How did they arrive at such a conclusion?

First, Miss Jourdain became convinced that Miss Moberly had seen the ghost of Marie Antoinette and that both of them had seen the ghosts of her friends and employees. When Miss Jourdain asked acquaintances if they had heard any stories about ghosts at the Petit Trianon, a French friend told her that on a certain day in August Marie Antoinette could be seen sitting outside the Petit Trianon, wearing a light hat and a pink dress.

"And," her friend continued, "the entire place is haunted with the people who used to be there with her."

You might wonder who Marie Antoinette was and what she had to do with a stroll taken by two English women. Versailles was once the residence of French kings, and one of them, Louis XVI, had given the Petit Trianon to his wife, Marie Antoinette, in 1774, as her own private getaway at Versailles. But Marie was known for her extravagant taste and arrogance during a time when France suffered from an economic crisis. A poor harvest in 1788, along with a government heavily in debt to foreign nations, resulted in a large increase in the price of bread. That angered the ordinary citizens of France, who demanded a change in the French government, beginning what came to be known as the French Revolution. And Marie Antoinette became a despised symbol of a wealthy government that had lost touch with its people.

Through research, though, the two women traced the history of Marie Antoinette, date by date. They learned that at the height of the French Revolution, both she and Louis XVI were taken from Versailles by a mob of angry citizens and forced to live at the royal palace at the Tuileries in Paris. A few years later, a crowd of citizens attacked the Paris palace and imprisoned them. Finally, they were beheaded in January 1793. What struck the women about their research was one date: August 10. Not only was this the date in 1792 that Marie and Louis XVI had been imprisoned, but it was also the day--109 years later--that Miss Moberly and Miss Jourdain had visited Versailles. Was this merely a coincidence, or did it suggest that their experience was real? This helped convince the women that they had traveled back in time.

Second, Miss Moberly and Miss Jourdain concluded that they had seen not the present Petit Trianon, but the Trianon as it appeared over a hundred years earlier. Between 1902 and 1904, Miss Jourdain made frequent trips to Paris--and Versailles--with her students. Each time she visited Versailles,looking for clues to the haunting, she was unable to find the gazebo and the bridge they had seen on their walk. Why should they be missing? Only, she suspected, if they had traveled back to an earlier time when the gazebo and bridge were present. Later, in July 1904, both Miss Jourdain and Miss Moberly were able to visit Versailles together. Not only could they not find the gazebo or the bridge, but they also noticed that the grounds were crowded with people, walking or sitting in the shade. This was quite different from their 1901 visit, when they saw only five people: the two gardeners, the hideous man at the gazebo, the running man, and the seated lady. Where had all the tourists been?

But to prove that they had traveled back in time, they had to uncover more information. By talking with workers at Versailles and by looking up information in libraries and bookstores, they found that:

-

neither the gardeners nor any other employees at Versailles wore gray-green coats and tri-cornered hats in 1901. However, the soldiers who guarded Marie Antoinette had worn such outfits.

-

there was no gazebo on the grounds of the Petit Trianon. However, the women discovered an old map that showed a gazebo-like building where they had seen one. It had been torn down long before 1901.

-

the hideous man with the rough complexion at the gazebo resembled the Comte de Vaudreuil, a close friend of Marie Antoinette, who had had smallpox.

-

the running man, dressed strangely for an August afternoon, was a messenger sent to the Petit Trianon to warn Marie Antoinette that a mob of French citizens was headed to Versailles. This happened on October 5, 1789, the last day that Marie Antoinette was allowed to spend there.

-

the woman sitting by the terrace of the Petit Trianon resembled a painting of Marie Antoinette, according to Miss Moberly.

This information convinced them that as they made their way to the Petit Trianon, they entered a "time warp" on the day Marie Antoinette was imprisoned in Paris. Even though Marie Antoinette was not at Versailles on August 10, 1792, she must have thought about returning there.

Did Miss Moberly and Miss Jourdain truly travel back in time to Marie Antoinette's Petit Trianon?

At the time, many people chose to believe their story, but not the scientific community. In one review of their book, Eleanor Sidgwick of the Society for Psychical Research in London wrote that the women could not be believed for two important reasons. First, the women were talking to each other and paying little attention to their surroundings as they walked through the grounds that day. This meant that they might have easily been mistaken about the episode. Second, they didn't record their experiences immediately after their walk in August 1901. By waiting three months to write about their adventure, they were forced to rely on distant--and perhaps unreliable--memories. Mrs. Sidgwick wasn't surprised that they couldn't retrace their route through the grounds; she concluded that their memories should not be trusted for accuracy. Today most researchers believe that the women invented most of their story.

How could the women have provided better proof?

-

They should have agreed immediately that something strange had happened that day.

-

They should have each written an account of their walk before discussing any details with each other.

-

Besides researching the history of the Petit Trianon, they should also have researched the present. Why, for example, didn't they try to find out if the men (the gardeners and the running man) were employees of Versailles in 1901? Shouldn't they have asked to meet the people who were working on the grounds of the Petit Trianon that day? Only by ruling out this possibility does the possibility of their time trip become more believable.

Copyright © James M. Deem. Adapted from How to Travel Through Time (New York: Avon, 1993). All rights reserved.