Time Travel Stories

by James M Deem

Back to Main Time Travel Stories

Recommended Books

About the Aberfan Disaster

In early October 1966, a ten-year-old Welsh schoolgirl named Eryl Mai Jones had something important to tell her mother.

"Mummy," she said, "I'm not afraid to die."

"You're too young to be talking about dying," her mother said. "Do you want a lollipop?"

"You're too young to be talking about dying," her mother said. "Do you want a lollipop?"

On October 20, Eryl Mai woke up after having a memorable dream.

"Mummy, let me tell you about my dream last night," she said.

"Darling, I've no time now. Tell me again later."

"No, Mummy, you must listen," she said. "I dreamt I went to school and there was no school there. Something black had come down all over it.

Her mother thought nothing more about the dream. After all, they lived in Aberfan, Wales, a poor coal-mining town. Perched high on a hill overlooking Aberfan was a coal tip, where waste from the mining process was dumped. The Aberfan coal tip caused many residents of the town to worry for their safety. So when Eryl Mai's mother heard her dream, she may have concluded that her fear of the ever-present coal tip had provoked it.

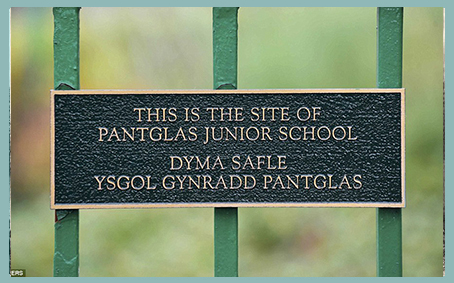

Eryl Mai went off to Pantglas Junior School that day as usual. Nothing unusual happened. The next day, Friday, October 21, she did the same. But at 9:15 that morning, the coal tip gave way, sending tons of coal sludge, water, and boulders to the village below. The avalanche mowed down everything in its path, including stone houses and trees, and swept toward the Pantglas School, where it crushed the back of the school.

In all, 144 people were killed, most of them children at the school. Eryl Mai Jones was one of the victims.

Had her dream provided a glimpse of a tragedy in the future? Or was it merely a coincidence?

Dr. John Barker, a psychiatrist in a nearby town, was curious to discover if anyone had had a precognitive dream or vision about the Aberfan disaster. He persuaded a newspaper to run an article asking people to send in a written account of any precognitive experience related to Aberfan. Altogether, he received seventy-six letters, but many seemed too vague to have anything to do with Aberfan. He selected the cases that seemed believable. Then he made sure to ask each correspondent to supply him with the names-and addresses of anyone who knew the details of the dream or vision before the disaster had occurred. Only by asking friends and family of the correspondent for confirmation could Barker be sure that the correspondents were telling the truth.

Eryl Mai's experience came to light through Barker's appeal for precognitive cases. Although she was the only schoolchild in Aberfan to have a future vision, she wasn't alone in her precognitive experience. However, most of those who wrote had never heard of Aberfan, didn't live near it, and had no connection to it in any way.

One woman, Carolyn Miller, had a vision of the disaster on the evening of October 20. In her mind she saw:

an old school house nestling in a valley, then a Welsh miner, then an avalanche of coal hurtling down a Mountainside. At the bottom of this mountain of hurtling coal was a little boy with a long fringe looking absolutely terrified to death. Then for a while I "saw" rescue operations taking place. I had an impression that the little boy was left behind and saved. He looked so grief-stricken. I could never forget him, and also with him was one of the rescue workers wearing an unusual peaked cap.

She met with some women from her church that night and shared her vision with them. She also told a neighbor the next morning at 8:30 what she had seen. She was stunned to hear about the disaster, but even stranger is what she saw while watching television two days later. That night she was watching a program about the Aberfan tragedy when she saw both the terrified boy from her vision and the rescuer.

This raises the question: Did she have a vision of the Aberfan tragedy or of the television program that summarized it? It may well be the latter.

Another precognitive experience related to Aberfan was related by Mary Hennessy. She wrote Dr. Barker to say that she had dreamed about Aberfan the night before the tragedy. In her dream, there were a lot of children in two rooms. Eventually, they moved to a larger room, where they seemed to be playing in small groups:

At the end of the room there were long pieces of wood or wooden bars. The children were trying somehow to get over the top or through the bars. I tried to warn someone by calling out, but before I could do so one little child just slipped out of sight. I myself was ... watching from the corridor. The next thing in my dream was hundreds of people all running to the same place. The look on people's faces were terrible. Some were crying and others holding handkerchiefs to their faces. It frightened me so much that it woke me up.

The dream was so vivid and terrifying she was worried that it meant harm would come to her two young grandchildren. Early the next morning, she called her son and daughter-in-law at 8:45 and explained her dream.

"I am very worried because the dream was about children. It makes me think about the girls," she said, referring to her granddaughters. "I know I dreamed about schoolchildren, but just take special care of them, please?"

Despite the large number of precognitive experiences related to the Aberfan disaster, however, no one's vision or dream provided enough details to have prevented the tragedy. That is one of the unfortunate truths about precognition: Although glimpses into the future are possible, the information isn't specific enough to allow most people to stop a disaster from happening.

Copyright © James M. Deem. Adapted from How to Travel Through Time (New York: Avon, 1993). All rights reserved.