S ometime during the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt, around the year 1100 B.C., an Egyptian priest named Nesyamun (also Natsef-Amun) died.

As was customary at the time, his body was mummified and then placed in a tomb in an area of Egypt called Deir el Bahri. There, Nesyamun's mummy remained for almost 3,000 years until A.D. 1823, when M. J. Passalacqua, an "antique dealer" who was reportedly more of a grave robber, found it along with many others. Passalacqua specialized in clearing out Egyptian tombs and selling their contents.

Shortly, Nesyamun was offered for sale along with other items from Deir el Bahri. A group of people from Leeds, England, who had formed the Leeds Literary and Philosophical Society, arranged to buy Nesyamun so that they could study his remains scientifically. Members of the Leeds Society were wealthy enough to erect a museum that contained laboratories and meeting rooms. They had also hired a curator to oversee the museum's collections. Members of the museum had already studied one mummy. But when they had unwrapped it, they were dismayed to find that it had been almost entirely eaten by beetles. They hoped that Nesyamun's mummy would be in better condition when it arrived in Leeds in 1828. If the outer coffin that enclosed it was any indication, they were not going to be disappointed.

Shortly, Nesyamun was offered for sale along with other items from Deir el Bahri. A group of people from Leeds, England, who had formed the Leeds Literary and Philosophical Society, arranged to buy Nesyamun so that they could study his remains scientifically. Members of the Leeds Society were wealthy enough to erect a museum that contained laboratories and meeting rooms. They had also hired a curator to oversee the museum's collections. Members of the museum had already studied one mummy. But when they had unwrapped it, they were dismayed to find that it had been almost entirely eaten by beetles. They hoped that Nesyamun's mummy would be in better condition when it arrived in Leeds in 1828. If the outer coffin that enclosed it was any indication, they were not going to be disappointed.

Nesyamun's body was enclosed in two coffins. The outer one was constructed of sycamore, in the shape of a man with his arms crossed on his chest. The face, however, did not belong to Nesyamun. At the time of his death, pre-made coffins with standard male and female faces carved on the outer coffin were sold. Only members of the royal families had coffins tailored to their own likeness.

Soon after the mummy arrived in Leeds, members of the society conducted an autopsy on it. After removing the body from the coffins, they began to unwind the linen wrappings. They discovered that Nesyamun was wrapped in at least forty layers of linen. As was common, the outer wrappings were made of excellent-quality, finely woven narrow linen. But the cloth became increasingly coarser and wider for the inner wrappings. Between some of the wrappings, jewelry and ornaments were found. The last layer of bandages did not reveal Nesyamun's face or body immediately, since a one-inch layer of spices had been placed between the skin and the linen. The spices had also been used to fill the abdominal and chest cavities. His mouth and throat were also filled with a powder made from vegetables, and his cheeks were filled with sawdust to maintain the natural shape of the face.

On that day in 1828, almost three thousand years after Nesyamun's death, the autopsy team could smell cinnamon in the air around them as they removed the last layer of bandages. When the spices were removed, they saw the body of a priest: his head, eyebrows, and beard had been shaved. William Osburn, one member of the autopsy team, noted that his skin was gray, in good condition, and "soft and greasy to touch."

The team inspected him carefully and saw that the embalmers had used a classic and very elaborate method of mummification. They had removed his internal organs, treated them with a saltlike substance called natron, put them into packages, and replaced them in his abdomen. The brain had been removed (as was common in the process of mummification used at the time of his death) through the right nostril. The inside of the skull had been filled with powdered spices.

Perhaps the team's most striking discovery was the fact that Nesyamun's tongue was sticking out of his mouth. This was quite unusual; only one other mummy has ever been discovered with this feature. No one could decide if this bizarre quality was related to his death. Although the autopsy suggested that he had died at middle age, the nineteenth-century scientists had no idea what had caused his death.

Despite the 1828 autopsy, many questions about Nesyamun remained unanswered.

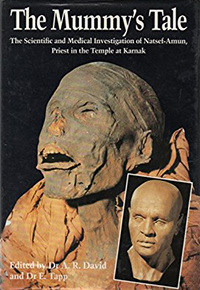

In 1989, members of the Manchester Egyptian Mummy Research Project, headed by Rosalie David, were asked to conduct a second autopsy using nondestructive techniques. Their findings were reported in a book entitled, The Mummy's Tale.

In 1989, members of the Manchester Egyptian Mummy Research Project, headed by Rosalie David, were asked to conduct a second autopsy using nondestructive techniques. Their findings were reported in a book entitled, The Mummy's Tale.

Over 160 years after the first autopsy, great refinements had been made in medical science, even medical science applied to mummies. The team was curious to know what caused Nesyamun's tongue to protrude.

On closer examination, they discovered that his tongue appeared to have broken off sometime during the mummification process. The embalmers then covered it with glue so that it might be reattached. But this didn't explain why his tongue protruded.

The team considered three possibilities:

-

Nesyamun had a tumor.

-

Nesyamun was strangled.

-

Nesyamun had been stung on his tongue by a bee, which caused him to choke to death.

The team ruled out the first two possibilities. The tongue appeared to be no larger than normal; when the scientists looked at cells from it under a microscope, they did not find any cancerous ones. They also ruled out the possibility that he was strangled, since his neck had no marks whatsoever.

That left the possibility of a bee sting or some other type of allergic reaction. Because bodily fluids were drained from the body during mummification, there was no way to check for an allergy. Although the scientists could not reach a definite conclusion, this possibility could not be discounted.

Nesyamun's mummy is displayed at the Leeds Museum in Leeds, England.

Copyright © James M. Deem. Originally published in How to Make a Mummy Talk (Houghton Mifflin, 1995). All rights reserved.

Other Mummy Stories by James M Deem

Curse of Tut's Tomb  Elmer McCurdy

Elmer McCurdy  The Franklin Expedition

The Franklin Expedition  Lemon Grove Girl

Lemon Grove Girl

Lindow Man, Bog Body  Nesyamun

Nesyamun  Rosalia Lombardo

Rosalia Lombardo

The Titanic Mummy  Tollund Man, Bog Body

Tollund Man, Bog Body

Tollund Man, Bog Body

Tollund Man, Bog Body